When the Society of Trained Masseuses (now the Chartered Society of Physiotherapy) was formed in the UK in 1894, its founders set out a number of rules for professional practice1.

Although the massage scandals in the summer of 18942 had highlighted the need for a professional masseuse, the founders of the new Society were keen to ensure status and standing in the marketplace through an affiliation with the medical profession.

The problem of quackery*, and in particular rising sales of patent medicines in society in the latter part of the 19thcentury, (negatively affecting business for physicians and general practitioners), provides some rationale for the inclusion of a rule prohibiting the sale of drugs by members of the Society.

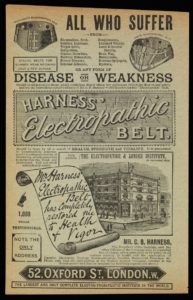

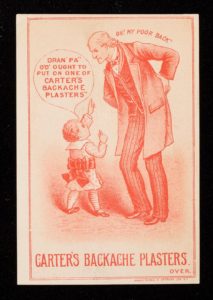

Patent medicines and appliances of unproven efficacy were widely accessible in the marketplace in England after 18803. Advertisements accompanied by persuasive testimonials and endorsements from professionals were available on mass3. ‘Cures’ for backache (among other things), such as Harness’electropathic belt (circa the 1890s) – ‘guaranteed to imperceptibly generate a mild continuous current of electricity’ and Carter’s backache plasters (circa 1900) (containing smartweed and belladonna (deadly nightshade) suggested by a young boy to his grandpa, certainly will have had some appeal.

Aside from the lack of strong state regulation and good-quality clinical trials to prevent the use of un-tested ‘quack’ therapies, part of their attraction lay in the fact that they were much more conservative than the alternative. Medicine in the 19thcentury was particularly ‘heroic’, with doctors prescribing highly toxic drugs and operating without anaesthetic or antibiotics. People were happy to try many unconventional remedies if it meant avoiding purging, bleeding and the scalpel. But does that same logic apply today?

The issue of promoting questionable treatments has come to the fore again this month, in an update from the authors of the 2018 Lancet Low Back Pain Series4. Some of the less positive highlights since the 2018 publications include the continued delivery of low value healthcare to people with back pain across the world. Passive non-evidence-based interventions continue to be advised and offered, whilst aggressive marketing in some countries is influencing the availability and use of ineffective (and potentially harmful) drugs and medicines.

References:

- Barclay, J. (1994) In good hands. The history of the Chartered Society of Physiotherapy 1984-1994

- Editorial. (1894) Immoral “massage” establishments. British Medical Journal2(1750):88

- Loeb, L. (2001) Doctors and patent medicines in modern Britain: Professionalism and consumerism. Albion: A Quarterly Journal concerned with British Studies33: 404-425.

- Buchbinder, R., Underwood, M., Hartvigsen, J and Maher, C. (2020) The LancetSeries call to action to reduce low value care for low back pain: an update. Pain161: S57-S64