In 1921, when the presence of men within the massage profession was still largely frowned upon, Matthew Guinan was the 77th masseur to be registered with the New Zealand Masseurs Registration Board. His registration was granted under the Board’s amnesty for anyone who had practiced as a masseur in New Zealand for the three years preceding the enactment of the Masseurs Registration Act 1920, but it is the manner of Guinan’s work that makes for particularly interesting reading and suggests that he was a man who would leave his mark on the profession.

Guinan was born in Dundee, Scotland and after emigrating, settled with his wife Betsy Ann in Otago, New Zealand in 1901. He was a powerfully strong man, described in his obituary as being “as strong as a lion and figured in tug ’o-war tests of strength popular about 30 years ago”. His first appointment was as a blacksmith at McIntyre’s Station, Waikoikoi, but he also practiced as a hairdresser, a herbalist, and at various times as a horse-masseur.

He built his reputation as a healer first with animals, but increasingly with people. In May Brownlie’s (1992) book Kismet for Kelso the author records that, “In the house at Kelso, he was consulted on all manner of problems, some well outside the field of a vet [sic] today. Mrs. Russell remembered the fearsome ordeal she suffered, when her mother took her ‘down the long hall, and into a side room. I had a bad tooth, and had cried for nights with toothache. Matt Guinan had that tooth out in a trice, and didn’t I yell! There was no nonsense with him’”.

“Matt’s Hospital” as it came to be known, became so popular that the boarding houses in Kelso flourished with the patronage of his clientele. Mrs Owen Duff, a resident in the town, commented, “‘I recall, very clearly, walking to school on fine sunny mornings and as we came over the bridge, at the bottom of the hill, we could see tiny groups of people the whole length of the main street. Some walked with the aid of a stick, others were on crutches and some were being pushed in wheelchairs. All were attending Matt Guinan and were taking the exercise he ordered between treatments” (Brownlie, 1992).

By now, Guinan was practicing massage almost exclusively on people. But he was also an entrepreneur and had a little chemist’s shop at the front gate where he sold “Guinan’s Balsam” (“Rheumatism, Sciatica, Lumbago, and all kindred afflictions are banished by using our Balsam. ‘Nil Desperandum’ would be a true motto indeed for this preparation. No man or woman need despair. Let the malady be of ever so long standing, our Balsam will afford relief”), massage oil (“…one of the most marvellous Oils [sic] that has ever been used on the human frame”), Indigestion and Bilious Remedies, Pile Ointment (not to be confused), Liniment, and the famous “Pink Ointment”, which was once used to heal completely the burnt hands of a child who had accidentally fallen on to a scalding hot range.

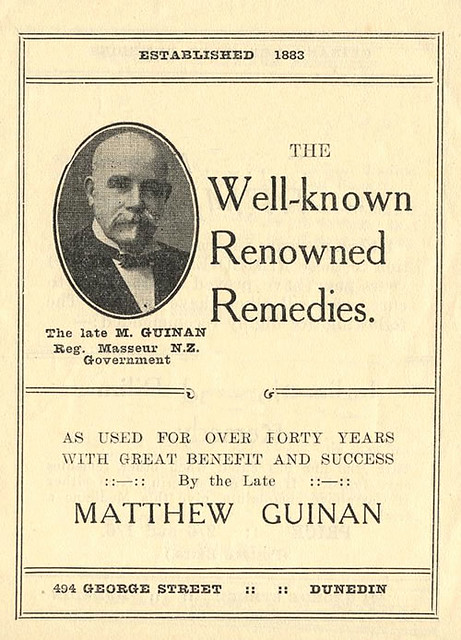

Guinan’s life was not without its tragedies. In 1910 the chemist shop burnt to the ground, and in the same year a patient who had been under treatment for a sprained ankle was found dead in his boarding house rooms. No blame was apportioned to Guinan, but within two years the Guinan family had moved to Dunedin where Matt opened a practice at 494 George Street. Guinan travelled to England to develop his massage skills further and continued his practice with great success. It was said that, “He had magnetism in his touch, and was wonderfully successful in the treatment of sprains, bruises, and misshapen joints. Power…flowed from his hands. He massaged all of the body of a sufferer, and had special liniments”(Brownlie, 1992,)

His obituary ends with this statement: “Members of his family had been trained in the masseur’s art by [the] deceased, and no doubt some of them will carry on the business”. This was very prophetic because Guinan’s other legacy was to begin a dynasty of New Zealand masseurs and physiotherapists that, so far, runs to four generations. Matt’s daughter and son-in-law, May and Cliff Weedon graduated from the Dunedin School in 1924, studying as a couple while the school observed strict rules over separation of male and female students. Their son, Frank Weedon, qualified as a physiotherapist in 1949, the year that the profession became officially known as “physiotherapy”. Frank was the first graduate of the physiotherapy teacher training program in Dunedin in 1964 (prior to that student teachers had to travel to England for their training), and worked at the School for more than 30 years. Frank’s daughter-in-law continued the family tradition, and works as a physiotherapist today.

Matthew Guinan was quite clearly an extraordinary man. He was also a showman, an entrepreneur, a salesman and an innovator. His practice ranged from dentistry to massage, manipulation to herbalism, hairdressing to farriering. He died at 70, quite suddenly, and was much missed by his family and legions of patients. He did, however, leave an unparalleled legacy in the generations of masseurs and physiotherapists that followed him.

NB: Originally written as part of the New Zealand Centenary History Project.

References:

Brownlie, M. 1992. Kismet for Kelso. Gore: Gore Publishing.

Comments are closed.

Thanks Dave.. I always look forward to your postings and really enjoyed this one. Keep up the great work!

Great story, obviously there is a natural progression from blacksmith to masseur !, most of us took generations to achieve that transition.