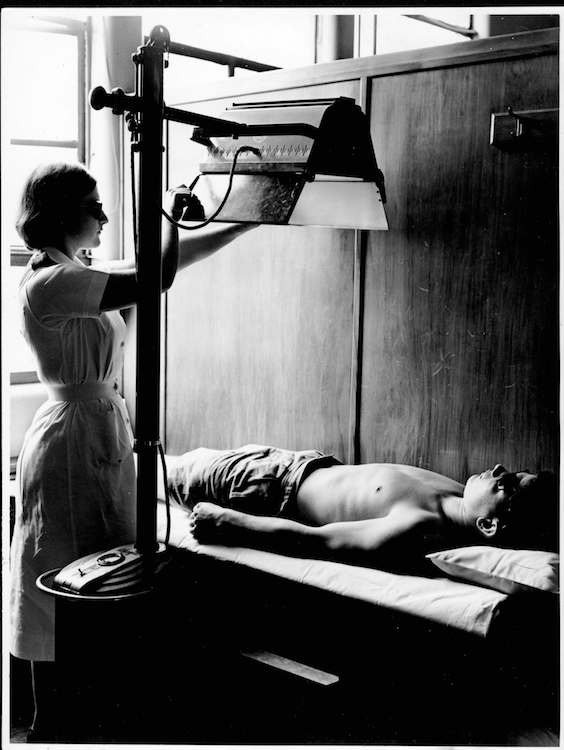

Physiotherapy has a long history with light therapy. Throughout much of the 20th century, light therapies were an integral part of the therapists toolkit. And actinotherapy – or the therapeutic use of artificial non-ionising radiations, especially ultraviolet light and infra-red (Beckett 1955, 1) – has formed perhaps the largest part.

Light therapies were used for conditions as diverse as abscesses, acne, anaemia, arthritis, bursitis, colds, dementia, diabetes, eczema, fibrositis, fractures, gangrene, gout, impetigo, lumbago, manic depression, mastitis, otitis media, psoriasis, rickets, ringworm, sacra-iliac strain, schizophrenia, sinusitis, tennis elbow, tuberculosis, and corneal ulcers, and specialists practiced in dermatology, paediatrics, rheumatology, and general medicine.

Something of the importance of light therapies can be seen in Faviola Creed’s recent review of Tania Woloshyn’s book Soaking up the Rays and an excerpts from the review is included here:

Soaking up the Rays presents one of the first monographs to examine the controversial histories and visual cultures of light therapy in Britain. Tania Woloshyn explains a wide variety of light therapies available from the late 19th to early 20th century and the illnesses (both medical and aesthetic) that they treated. Woloshyn’s purpose is not to measure their ‘success’. Instead, she evaluates both the changing historical contexts and visual ‘representations’ of ultraviolet technologies of health and beauty.

Both Simon Carter and Annie Jamieson have published on British actinic histories, but their works did not contextualise the visual cultures in such detail.1 Woloshyn’s book is certainly relevant for readers of public health and policy; she regularly refers to the British populations’ fixation with suntanning and skin cancer (evident by the reoccurring links to contemporary Cancer Research campaigns (pp.256–57)). The great spread and depth of her visual analysis builds on the academic histories of medicine, health, art and early 20th-century Britain. Woloshyn, however, provides a valuable model framework to be developed by researchers from many other disciplines that apply ‘close looking, critical analysis, and much contextualisation’ to images that are ‘problematic: confounding, ambiguous, and downright odd’ (p.21).

Woloshyn’s structure accentuates the significance of her visual culture approach. Each of the four main chapters is ‘driven by an image, or set of images and objects’ (p.37). This framework provides clarity for readers whilst allowing Woloshyn to unravel the contradictory ‘unclear and unstable messages’ from medical, popular and commercial groups, teasing out the ‘competing voices and interests’ (p.7) from a wide range of textual and visual sources. These include private and public archival collections of photography (mostly from hospitals), the print press, medical journals, advertising ephemera (especially Hanovia and Ajax products), lamps and goggles. Many of the captured ‘objects’ and ‘subjects’ are ‘bizarre, charming, glamourous, silly, and pornographic’; they can be ‘disturbing or explicitly sexual’ (p.16). When addressing these often-provocative images, Woloshyn writes both compassionately and sensitively, demonstrating an empathetic approach that historians should consider when writing on bodies and ‘invasive’ technologies.

In Chapter Two (‘Dosing sunburn’), Woloshyn evaluates documentary photographs of sunburn caused by ultraviolet light. She begins by contextualising a photograph of Danish researcher Dr Niels Finsen’s irradiated forearm from 1893 and explains how physicians were experimenting on their own skin to create a model of standardised treatment for their patients and promoted it to international medical communities. Researchers struggled both to assess the therapeutic effects and to capture the visual evidence photographically. Revealing the beginning of the British populations’ ‘complicated and contentious relationship with actinic light’ (p.82).

Chapter Three (‘Light registers’) further exposes the complications experienced by photographers and medical organisations when trying to capture their desired representation of light therapy…

Chapter Five (‘Photogenic Suntans’) develops this theme further by exploring the ‘social and political significance’ behind an artificially produced suntan for Britain’s ‘avid’ consumers (p.190), touching on early 20th-century tensions of race and class. The final chapter (‘Dead points’) concludes with an exploration of ‘light therapy’s numerous historical dead ends’, particularly in the limits of our understandings and the remaining unanswered questions of light therapy, stemming from the socio-political contexts.

Accompanying Woloshyn’s textual interpretations is a wealth of expressive imagery, conveniently and clearly formatted and beautifully reproduced. Her comprehensive footnotes and bibliography also provide valuable referencing points for researchers who explore similar themes. In summary, Soaking up the Rays displays a reflective methodology and meticulously detailed approach to analysing visual cultures. Woloshyn’s transferable toolkit can be both studied and applied by researchers to evaluate their own contentious histories and complex layers of visual representation.

Footnotes

1 Simon Carter, Rise and Shine: Sunlight, Technology and Health (Oxford: Berg Publishers Ltd, 2007); Annie Jamieson, ‘More Than Meets the Eye: Revealing the Therapeutic Potential of “Light”, 1896–1910’, Social History of Medicine, 2013, 4, 715–37.

References

Beckett, R. H. (1955). Modern actinotherapy. London: William Heinemann.

Creed, F. (2019). Review of Soaking up the Rays. Social History of Medicine, Volume 32, 2, May 2019, Pages 426–428, https://doi-org.ezproxy.aut.ac.nz/10.1093/shm/hkz005

Woloshyn, T. (2017). Soaking up the Rays, Manchester: University of Manchester Press. ISBN 978 1 7849 9512 6.