There are different ways to learn about (physiotherapy) history as a wide variety of sources answer questions about the past. Historians differentiate between primary sources, i.e. sources that have survived from the past, and secondary sources, i.e. accounts of the past that are written at a later period of time.

As far as primary sources are concerned, historical research relies heavily on written sources like administrative texts, official documents, private letters, diaries or memoirs, books, newspaper or journal articles. These sources typically provide detailed information and explicate a specific viewpoint or interpretation of past events.

By comparison, the meaning of historical objects, or artifacts, may be less straightforward. But through their materiality and their symbolic meaning, they can represent another way of approaching the past and show us another kind of history. According to museum experts Steven Lubar and Kathleen Kendrick,

Artifacts are the touchstones that bring memories and meanings to life. They make history real. Moreover, it is a reality that can and should be viewed from different perspectives.

As a consequence, they emphasize the potential of artifacts to:

- tell their own stories,

- connect people,

- mean many things,

- capture moments and

- reflect changes.

Thus it is not surprising that the International Physiotherapy History Association (IPHA) has started a project on 100 Objects of Physiotherapy. But where are such objects stored and made accessible to the public?

Here are two examples of museums relevant to physiotherapy history from Germany:

Deutsches Hygiene-Museum in Dresden (https://www.dhmd.de)

The prehistory of the Deutsches Hygiene-Museum dates back to the (social) hygiene movement at the end of the 19th century. Following the success of the First International Hygiene Exhibition (1911), which attracted more than five million visitors to Dresden, the museum was intended to impart knowledge about human anatomy and address issues of proactive health care and diet. Even today, one of the museum‘s most prominent exhibits is the Transparent Man (1927), representing the reification of modernism’s image of the human being and conveying faith in the link between science, transparency, and rationality.

In the room dedicated to “Movement“, models explaining human musculature and fitness equipment from the nineteenth century used to strengthen muscles are on display and various installations offer visitors the opportunity to test their own ability to move. In this way, the museum not only conveys theoretical knowledge about the human body, but also enables visitors to experience the body and raises awareness of the need for sufficient physical exercise.

In the online collection you can search for all types of materials from the past relevant to physiotherapy history. Here are just two examples:

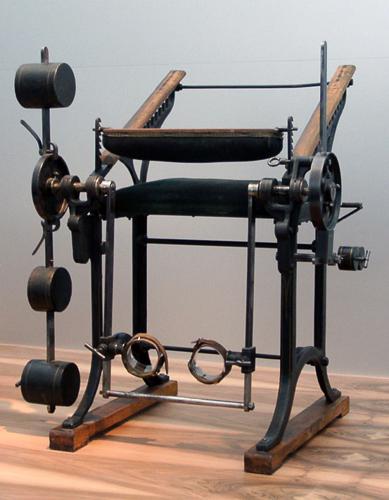

Apparatus for knee bending and stretching developed by Gustav Jonas Zander, fabricated in Germany between 1905-1914 (Creative Commons Licence)

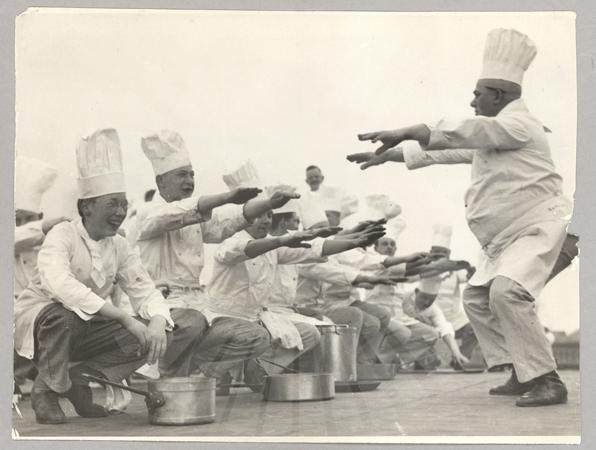

Photo “Köche brauchen Bewegung” (Cooks need movement) published in Vossische Zeitung from 25.5.1930 (Creative Commons Licence)

Deutsches Orthopädisches Geschichts- und Forschungsmuseum in Frankfurt am Main (https://www.kgu.de/einrichtungen/kliniken/klinik-fuer-orthopaedie-friedrichsheim/forschung-und-lehre/deutsches-orthopaedisches-geschichts-und-forschungsmuseum-bildergalerie/)

Zander resistance apparatus

Germany’s only museum on the subject of orthopedics was founded in Würzburg in 1959 following the orthopedic congress which was held there at that time. Würzburg is also considered to be one of the cradles of conservative and operative orthopaedics in Germany. In 1816, the first sanatorium for the crippled was established here, and corrective bone operations were already being performed just 20 years later. For reasons of space, the museum moved to Frankfurt am Main in 1995.

Amongst other things, the orthopaedic museum provides insight into diseases of the locomotive organs, the supply of prostheses, the history of orthopaedics and its predecessors as a scientific discipline and the social history of “cripple care“ in Germany. It collects and preserves objects and assistive devices that serve or have served for the prevention and treatment of diseases or changes in the human body, endoprostheses, implants and anatomical specimens etc.

Video in German about the museum’s collection and research interests (2015): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ejfx1f6ujqU&t=5s

It would be interesting to learn about more such collections of objects from physiotherapy history from around the world.

Reference:

Lubar, Steven & Kendrick, Kathleen. Looking at Artifacts, Thinking about History. http://www.smithsonianeducation.org/idealabs/ap/essays/looking.htm

Do you know what this and who might be interested in it. My grandfather used it in the 40’s

Can’t seem to load picture? Email me for picture